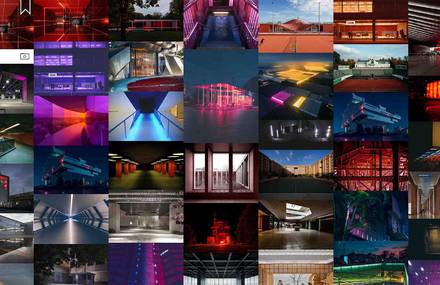

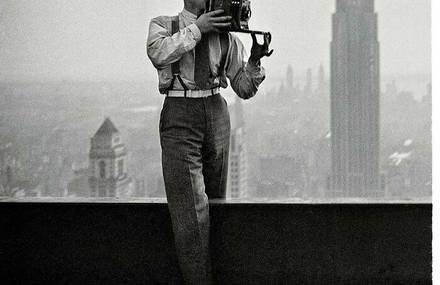

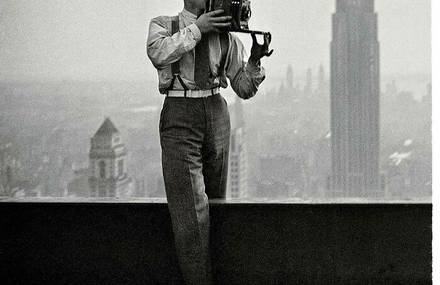

Photographer and curator, Guillaume Tomasi is based in Montreal. His work revolves around the story through the image, but also people, places and memories. In his series Chrysalis, he presents « anonymous stories about intimate events that changed people’s worldview »

How and when did you start photography?

I always wanted to do something with my hands. I tried drawing, music and during my studies, I learned to create animations by coding. It was a very creative world, very demanding and very stressful. I liked the idea of being able to express myself by the code, but I had to meet the requirements of customers. So very quickly, it was a brake on my creativity. Leaving France for Canada in 2010, I discovered, a few years later, the work of Julien Coquentin (“Early Sunday morning”). His images impressed me because I knew the streets and neighborhoods he had photographed.

How did the Chrysalises idea come to your mind?

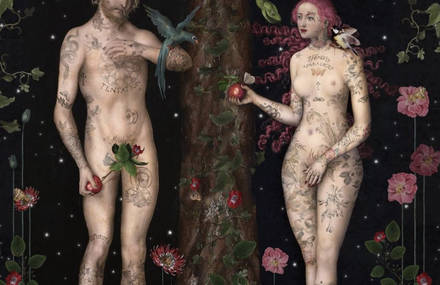

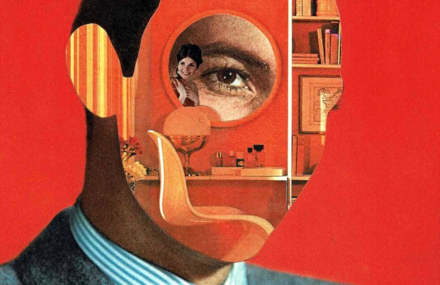

As often, the original idea was born from an anecdote. My son, 2 years old at the time, had a big fever. In the middle of the night, he was in tears when I entered his room to console him. He still had his eyes closed when he said, “Where are the butterflies?” He had fallen into a deep sleep just after. These were the only words he said that night. No longer finding sleep, my mind extrapolated around this phrase and around the butterfly’s face.I also remembered that my grandfather told me that if you saw a butterfly flying, it meant that nature was doing well. The question that my son asked me led me to think about how we discover, in our lifetime, that the world is not exactly as we have been taught. When would he discover that his vision of the world would certainly be harder and more brutal than the one I had instilled in him? After finding my decisive moment, I became obsessed with knowing the events around me.

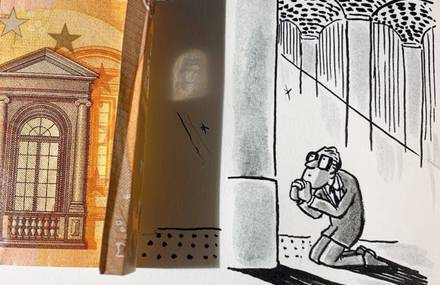

I had found my concept: to collect anecdotes about events that rocked the worldview of complete strangers. After browsing the social networks, writing ads, I decided to write sixty letters that I deposited randomly on the island of Montreal inviting recipients to tell me anonymously their decisive moment. The transcribed texts in my portfolio come partly from these correspondences and will be published in full in a photo book planned for the end of the year. Finally, the title “Chrysalises” refers to the figure of the butterfly and feeds the metaphor of evolution that these people undergo following these events. The chrysalis also plays on the symbolism of the cocoon that will be irretrievably broken by the vagaries of life.

What atmosphere did you want to convey?

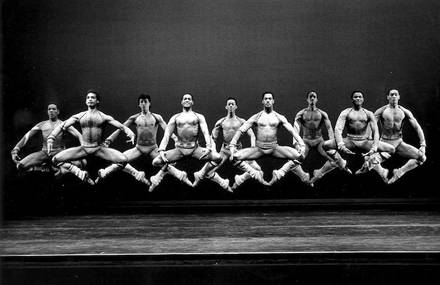

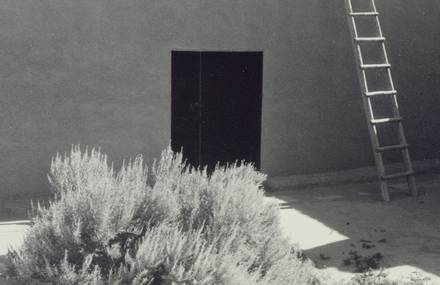

I wanted to develop a poetic and mysterious atmosphere where the daily is jostled and diverted in a subtle way. I like to give the opportunity to the viewer to interpret the images in many ways. Generally, I produce very open images, almost banal but which take another dimension when the next one appears.

What emotion do you want to convey to your public ?

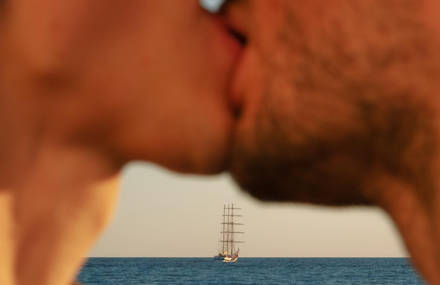

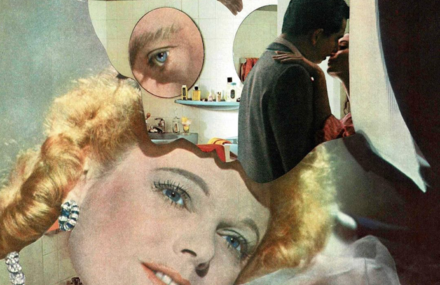

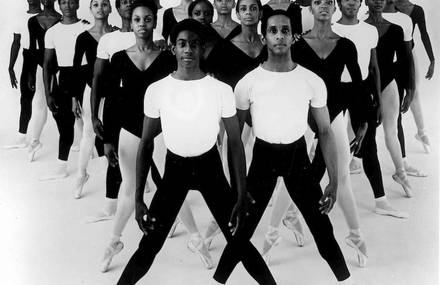

Through these anonymous stories and contemplative images, my goal is to reach the audience to reflect on their own life experience. Remember what was the pivotal moment that rocked his being in a completely different direction. I kept very abstract portraits where the faces are not necessarily recognizable to remain coherent with the anonymous character of the texts. The subjects photographed have mostly nothing to do with stories. This allowed me to prevent the public from linking stories to portraits.

Are the places and subjects represented all related to a particular story?

The images were produced at the same time as the anecdotes. They represent my interpretation of the theme. From this change of consciousness. I did not want them to be related to a story, so as not to lock them into a framework of interpretation. On the other hand, I am fully aware that juxtaposing them with the texts brings them a completely different narrative context. This will not be the case in the photo book I will publish soon.